After 25 years of research, we’re starting to get a clearer picture of what helps candidates win. But are we paying attention to the researchers or just doing what we’ve done?

In 2008, the Obama team rewrote the book on modern campaigning. Leveraging a wave of enthusiasm, the Obama campaign harnessed tens of thousands of volunteers, gathered reams of voter data, then used some reasonably basic targeting and fanned an army of volunteers throughout the country to knock on doors. Nothing reorganizes everything we know in politics like doing something new and then winning. So after 2008, books were written, companies were created, and a new conventional wisdom took root among political operatives that says that a strong ground game is an imperative to winning an election.

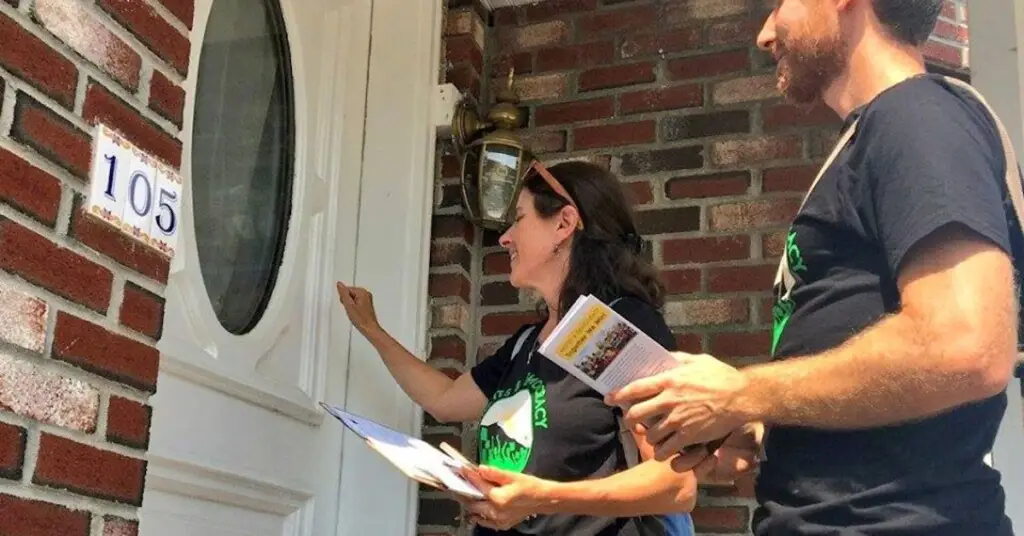

It’s important to distinguish between two different purposes of any political campaign tactic. One purpose is persuasion: convincing a voter to support a specific candidate (or issue). The other purpose is turnout: getting people who are already persuaded to support your candidate to then go and actually vote. This second part is referred to as GOTV (aka, get out the vote). The bulk of any GOTV effort is made up of phone banking and door-knocking, which are collectively referred to as canvassing.

Every presidential campaign strategy since Obama has hewed closely to that blueprint (albeit sans Obama). The results would indicate that a large and well-funded ground game does not correlate to winning an election.

2016

In keeping with the new conventional wisdom, Team Clinton had a ground game in place that dwarfed Trump’s. On Labor Day 2016, just 2 months before election day, in the 15 key states, Clinton had three times the number of campaign field offices (291) than the Trump campaign (88). To take a highlighter to the differential, in 3 key states (NC, FL, and PA) the ground game comparison looked like either the Trump team wasn’t trying (or they knew something the rest of us didn’t).

| State | Clinton Offices | Trump Offices | Outcome |

| NC | 26 | 1 | Trump +3.6% |

| FL | 34 | 1 | Trump +2.2% |

| PA | 36 | 2 | Trump +0.5% |

(source PBS)

Note: The Trump team did expand the number of field offices in several states late in the election, including in PA and FL, but they still a fraction of the field presence as the Clinton campaign.

2020

Fast forward just one election cycle and everything is different. The Trump campaign, in a reversal of 2016, but in keeping with the president’s views on Covid, sent armies of volunteers to knock on doors. In contrast, the Biden campaign, adhering to a safety-first approach, discarded doorbelling, the tactic that had become the golden rule of campaigns. It wasn’t until October that the Biden campaign finally allowed limited door-to-door visits.

All that is to say that there was as much of a lopsided approach to the field campaign in 2020 as there was in 2016, just in the opposite direction.

For high-profile presidential races, the research is pretty clear and the answer is pretty close to never. High-profile races where there is a lot of familiarity with the candidates, canvassing has zero effect toward persuasion. For turnout, most studies have shown the effect to be closer to 1% but higher for some types of campaigns.

In non-presidential races, where the saturation and polarization subsides, it gets much more encouraging. And the farther you go down-ballot with actual candidates having in-person conversations, the bigger the impact. The research is all over the board, depending on exactly what campaigns were studied, how well the canvassers are trained and whether it’s a local, off-year, or presidential election year.

For example, research by Charles L. Baum and Mark F. Owens found a that canvassing by a candidate in a state house race increased that candidate’s vote by 3 percentage points. Other research has shown even more of an effect but these tend to be where there is a personal conversation, usually with the candidate, or a substantive conversation about an issue, in the absence of media saturation.

A large door-to-door operation is expensive. For large high-profile campaigns, a lot of the canvassers are often volunteers but it still requires offices in local jurisdictions and professional staffers to organize, train, and manage the canvassing efforts. Also, anywhere from 70%-90% of doors don’t even get answered, they usually leave behind a nice color-printed flyer that is nearly always thrown away with little more than a cursory glance and a sigh of relief for not being home at the time.

A lot has changed from 2008 to 2024. In 2008, Facebook’s ‘like’ button had not even been invented yet. Podcasts were fringe. And Netflix was sending CD’s in red envelopes. By 2024, facebook is now for ‘old people’, TikTok is the new facebook/twitter/myspace, and the percent of cable subscribers is shrinking faster than Boeing’s stock price.

Behavior and attitudes have changed too. Watching The Wire (best show ever) has somehow turned into streaming YouTube content on an iPad, while listening to a podcast and researching vacation homes on AirBNB.

Twenty years ago, we answered the (landline) phone when it rang. Now, we screen our mobile phones and reject unknown calls. Back then, we also answered our door. Today, we seem to have a mini panic episode when we hear an unexpected knock at the door.

Maybe that explains why the connect rate – the percent of actual conversations per door knocked – is so low. Most doorknockers report connection rates of about 5-15% of each door knocked.

Possibly becasue of the changes above, or possibly some other reasons, even that low efficacy has been declining. One recent study by the Analyst Institute, a progressive research organization, found that door-to-door canvassing had a statistically insignificant effect on voter turnout. Whereas earlier research was showing an efficacy between 1-3% (for high-profile races), more recent studies indicated that has declined to essentially 0.

It’s not just that it doesn’t work and costs a lot of money and time. It’s that we’re not investing in other tactics that might be more effective. Digital advertising and social media are two examples that have gotten a lot of attention. But were not pursuing these in an organized way that leads to our intended outcomes. What we’re doing now is more like those early years where you learn to color and just scribble as much color on the page as possible. In 2020 Biden mostly replaced door-to-door with massive phone banking but most all research shows phone banking has nearly zero effect on either persuasion or on turnout.

One tool/tactic that has been shown to have enormous effect is relational organizing, which involves being contacted directly by a person known to the voter – a friend, family member, someone from the community, etc. The influence of one’s personal network has long been known to be one of the most effective methods at both persuasion and voter turnout.

Network organizing, so far, has been hard to scale. As a result, it is not used very widely and, therefore, the data on it is scattered. In addition to being difficult to scale, it requires some infrastructure to be put it in place, which makes it inaccessible to most all down-ballot campaigns.

It’s impossible to tell the future (and only idiots try) but there is growing evidence that relational organizing or relational voter turnout can have a profound effect on turnout. The concurrent rise of social media / influencers make a confluence of these two seem like the holy grail of campaign tactics. What that eventually looks like is anyone’s guess. Politics changes slowly and conventional wisdom is hard to shake. We may have to go through a few more elections trying to avoid answering our door before we get there.

Sources:

Does personal door-to-door campaigning influence voters? Evidence from a field experiment. Charles L. Baum and Mark F. Owens (2023)

The Effect of Door-to-Door Canvassing on Voting Behavior: A Randomized Field Experiment. Journal of Politics. Bowers, J., & Ensley, M. J. (2012).

Does Door-to-Door Canvassing Work? Evidence from a Randomized Field Experiment. Journal of Elections, Public Opinion, and Parties. Curto, J. J., & Galiani, S. (2018).

The Minimal Persuasive Effects of Campaign Contact in General Elections: Evidence from 49 Field Experiments. American Political Science Review. Kalla, J., & Broockman, D. E. (2018)

Get Out the Vote: How to Increase Voter Turnout. Green, D. P., & Gerber, A. S. (2015)

ProgressiveLabs is a Social Benefit Organization, dedicated to helping down-ballot Progressive organizations run effective, optimized campaigns that win on Election Day.